If we are not afraid to adopt a revolutionary stance—if, indeed, we wish to be radical in our quest for change—then we must get to the root of our oppression. After all, radical simply means “grasping things at the root.”

Angela Davis

In July of 2020, amidst the coronavirus pandemic and Black Lives Matter protests and riots across the United States, I was filing for divorce. At 26 years old, my 5 year marriage had already been crumbling for the past 2 years. Messages found on my husband’s phone were the final push I needed to allow myself to let go. I was both relieved and aware that I would have a long emotional climb ahead of me. With no kids and no house, we quietly divided our possessions and cats among the two of us, paid a lawyer $500 to draw up paperwork for an uncontested divorce and by September it was all done.

By October, I decided to stop going to church for the first time in my life. Raised from birth in the Evangelical church, I found myself deeply disillusioned. Trying to attend church now, I felt only a deep void inside of me. Hadn’t I followed all of the rules and paths laid out for me to live a life glorifying God? What went wrong? Confused, angry, heart-broken, and bitter I made a conscious decision to turn away from the God and faith I felt betrayed by.

In the years that followed, I allowed myself to slowly begin re-examining long-held beliefs. I started seeing a non-Christian therapist (a first for me, though I’d had many Christian counselors or therapists in the past) who spent the majority of our sessions reminding me to be kind to myself. I devoured Glennon Doyle’s Untamed and found books and podcasts of others who, like me, found themselves deconstructing from Evangelical Christianity. I discovered core beliefs I didn’t want to continue holding. Some beliefs simply no longer made sense to me, and on an even deeper level, there were other beliefs that were actively harming me – making me smaller, more afraid, and less loving towards myself and others.

I also spent time focusing on my physical health. I had been deeply disconnected, not just with my spirit, but also my body. For a few months I counted calories and learned about how to eat in a more sustainably balanced way. Though I was never a big fan of physical activity, I started running and discovered a kind inner voice of encouragement that said unexpected things like: “You can do it! Just a little bit further! You’re doing a great job!” I shed excess weight, completed a 5K race (then promptly stopped running) and felt more comfortable and joyful in my skin.

It was in this transformed and more confident state that I found the courage to follow my long-time dream of moving to France. As a university student in 2015, I spent a semester abroad in Grenoble, France, at the foot of the Alps. Since then, I had nursed the desire to return and live there again (a dream I’d failed to get my ex-husband onboard with). With some perseverance and luck I began my new life in Grenoble in January of 2023.

With a metropolitan population of around 700,000, Grenoble is a surprisingly international city. Numerous universities and tech companies draw people from all over the world. Starting from zero, the friends I made most easily ended up being other immigrants. I enjoyed learning about the homes and cultures of friends from Italy, Brazil, India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Hungary, Morocco, etc… Growing up in the American Midwest of South Bend, Indiana, I’d had little interaction with people from other countries and cultures. The churches and school circles I existed in had been predominantly white. Surrounded by my new friends, I became acutely aware of just how much I did not know about the world and also discovered a deep curiosity and willingness to learn.

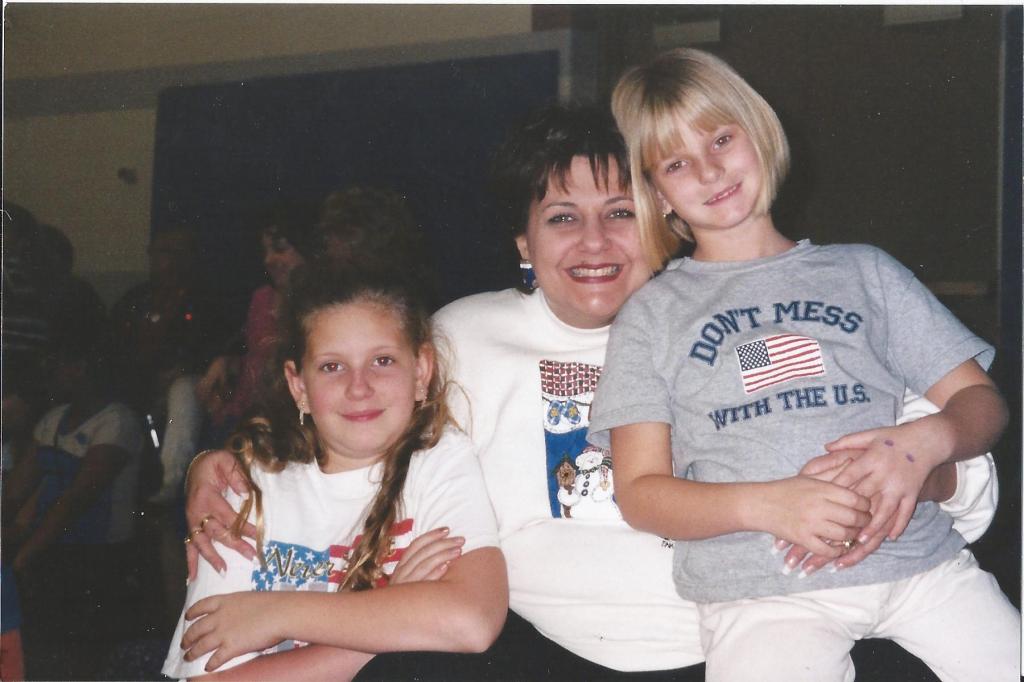

My political upbringing was somewhat rare in that while my parents were Bible-believing, fundamentalist Evangelical Christians, my mother was fiercely liberal. While we held progressive values at home, at the churches we attended it was assumed that the majority of people in attendance were politically conservative, though politics were not frequently discussed. In either case, to the best of my recollection, political issues and concerns discussed were only domestic in nature. While my parents talked very poorly of President Bush, in the wake of September 11th, our house, car, and clothing proudly displayed the American flag. We joined in with millions of other Americans to express a steadfast commitment to our country and a deep pride and gratitude for our good fortune of having been born in the land of the free. For my part, I never truly bought into patriotism. However, it’s equally true that I never dug further into my intuitive, strong dislike of American military might.

While many white Americans experienced moments of racial reckoning following the election of Trump in 2016 or the police killing of George Floyd in 2020, I remained by and large, uninformed and unengaged. In fairness to myself, I experienced the untimely death of my mother in January 2016, instability in my marriage from 2018, and our eventual divorce in 2020. So, while my heart was certainly grieved in both cases, I had neither the emotional nor mental capacity to truly process these events and the depth of their meaning, as my privilege did not require me to do so. Similarly, I did not have any tools or examples within my community of how to be moved to action. I intentionally distanced myself from news of tragic events, believing I could not even bear witness to the pain and heartbreak.

Within the Christian tradition in which I was raised, we believed that Satan and his evil forces were very active in the world around us. Though God was ultimately in control and had a plan for all things, these forces were responsible for any and all terrible events happening. One day, Jesus would return and establish the kingdom of God on earth and vanquish Satan once and for all. As I understood and practiced, our primary duty as followers of Jesus was to love and worship God, pray for the kingdom of God to be advanced, pray for the return of Jesus, and convert others to Christianity so they could take part in the advancement of the Kingdom and spend eternity with God.

An unspoken, but natural extension of these core beliefs is that we as Christians are not ultimately responsible for vanquishing the evils of the world. God is in control and Jesus will make all things right when he returns. So, when you see the news of the Sandy Hook school shooting, immigrant children separated from their parents and placed in cages, Breonna Taylor killed in her house in the middle of the night, or wars and famine in far off countries, you say a prayer. Maybe you shed some tears or send $10 a month through a Christian organization to an orphan in Africa. Then you remind yourself that God is in control and one day, justice will prevail. I do not wish to imply that these things hold no value but merely want to paint a picture of how I as a devout Evangelical viewed these matters. Ultimately, such tragedies were not affecting my predominately white, middle-class, American church community and therefore, were not given much attention.

At 18 years old, this is what I wrote in my journal on December 14, 2012 in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting where 20 children and 6 adults were killed:

The tragedy at Sandy Hook in Connecticut is so hard to see and hear about. It breaks my heart to see such evil and pain. I am so thankful that through it all, You are God and You are good. I pray that you would show up in that community and situation and be so faithful to turn things around for good. I pray that You would unite the church and through the church, the community. Speak to people in their pain and sorrow. Leave Your mark on the people in Newtown. They will never be the same, and that is certain, but I pray that they would be different because of all the work You do through this terrible situation. You are worthy of everything and I pray that even through this You would continue to receive glory and be worshiped. I pray this situation would make for stronger faith, not a loss of it.

Though my heart was extended in sympathy, I did not have the skills to process the true pain and anger of such senseless loss. Here, I used spiritual bypassing – spirituality to distract from and ease uncomfortable feelings. Ingrid Clayton writes for Psychology Today, “spiritual bypass is a defense mechanism. [It] shields us from the truth, it disconnects us from our feelings, and helps us avoid the big picture.” Rather than sitting with the pain of the situation or allowing myself to feel an appropriate rage at American gun violence, I moved immediately to how I believed god would be faithful and use the situation for good. It’s not that I think at 18 years old I needed to be lobbying for gun control (though there are certainly teenagers who can and do that kind of work) or that it is never appropriate to turn to spirituality when we’re having difficulty coping. However, by making a habit of disconnecting from my feelings and avoiding the bigger picture — not grasping at the root — my response to such tragedies and injustices remained the same throughout my 20s.

Things began to break open for me following October 7, 2023 and the acceleration of the ethnic cleansing of Palestine. For the first time, I was in community with people who cared deeply about issues of social justice on a local and global scale — friends from India and Pakistan whose countries and families had been personally harmed by colonization. These friends spoke with bold clarity about what Israel was doing in Gaza, why it was happening, and that it had been happening for over 75 years. I had known absolutely nothing about Palestine or Israel. Hearing these things paired with the live footage of the horrors inflicted on Palestinians in Gaza, I realized that I had some serious work to do if I wanted to understand what was going on.

Later that month, looking through Instagram, a thought struck me. I suddenly began scrolling quickly through my feed. I wasn’t looking to watch or read any posts. I was searching for any faces belonging to non-white individuals. I did not find them. So, that day I searched for a few Palestinian accounts from individuals, like Bisan Owda, or news from Gaza, like Hidden Palestine, and hit the follow button. As time went on, the more I engaged with this content and the more accounts I followed, the more accounts I saw from people of the global majority. If someone said something that sparked my interest even the tiniest bit, I would follow them. In this way, I began listening to perspectives and stories I’d never heard before and took my first intentional steps in deciding to let my heart break open.

In my journal on October 21, 2023 I wrote:

Sometimes the pain of the world threatens to drag me under… I can’t watch the news. I can’t confront and internalize the pain. It swallows me whole with helplessness… But today, I ask myself — how much can I take? How far can I push the walls of my heart to take in the suffering of others? To not close myself off to it but to share in it. So, I will do what I can to help hold your pain, whether I know you or not.

It was in this purposeful space, pushing open the walls of my heart to the pain of others, that I began to realize my ideas of the world, my country, and my place in everything were woefully incapable of handling what I was seeing, hearing, and learning — so I let it all crumble. I cannot understate how painful and difficult this was. Having deconstructed the faith I once rooted myself in, I struggled to find any hope. I floated as a ghost through months of deep depression, anger, and nihilism. I thought, “Nothing is coming to save us. We have to do it ourselves and we’re not doing it.” I devoured books and podcasts (and let’s be honest, Instagram posts/reels) about history and religion and capitalism and intersectional feminism, etc… in a desperate attempt to find some sort of knowledge or understanding to reorient myself during this terrifying freefall.

In February of 2024, I wrote this poem:

You are 29 years old when you wake up

When you start to see the world as it is

When you not only acknowledge but

Force yourself to bear witness to the tragedy of depravity

(We are not born depraved as you once were taught

But we are creatures carved out by pain

And so very susceptible to fear and hate)

You had spent some years slowly walking to the edge of your bubble

You are 29 years old when you let it pop

You discover that it was both a prison to keep you in line

And a fortress to keep the pain and humanity of others out

No fortress

No bubble

No shut eyes

You connect

You let your heart hold the pain your privilege protected you from

Your heart is stronger than you were led to believe

Your empathy is your super power

So you let it dance with what you have discovered in the awakening

Curiosity

Rage

Resistance

Love

You are 29 years old when you wake up

There is still so much to uncover

Because I was consuming so much content so quickly, It is difficult for me to pinpoint all the teachers from whom I learned during this time. Early on I found the work of Cole Arthur Riley and her wonderful Instagram account, Black Liturgies, where she shared quotes from many Black authors, artists, and activists like bell hooks, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, etc. Each of her posts was like a balm to my soul, meeting me in the grief and pain of broadening awareness to remind me that I was not alone — even as I felt a growing distance between who I had been and who I was becoming and the strain that placed on some relationships. Later, I got her book This Here Flesh: Love, Liberation, and the Stories that Make Us and also read bell hook’s All About Love. In the pages of both books, I experienced the surface of a self-love, kindness, and freedom that even my years of therapy and stacks of self-help and psychology books had not scratched.

On the Instagram page of the black online bookstore, Everyday is Juneteenth, I came across another book that was important in my journey — White Women: Everything You Already Know About Your Own Racism and How to Do Better by Regina Jackson and Saira Rao. Jackson, a Black American woman and Rao, an Indian American woman, are uninterested in sugar-coating or trying to protect the feelings of white women. As such, this book was blunt and sincere in its goal of trying to get white women to simply acknowledge their own bullshit and how racism and white supremacy factor into it.

This was my first interaction with work that specifically called out facets of whiteness culture. Broken open, I was ready for this kind of critique and a hard look at myself. At that time, American culture, life, and material consumption had been rolling on for, 5 months while an active genocide — funded in part by our tax dollars — was being streamed to our phones. This was the catalyst for me to understand for the first time just how deeply sick our society was and has always been. Sometimes I felt so much disgust, so much anger. I had nothing left to defend.

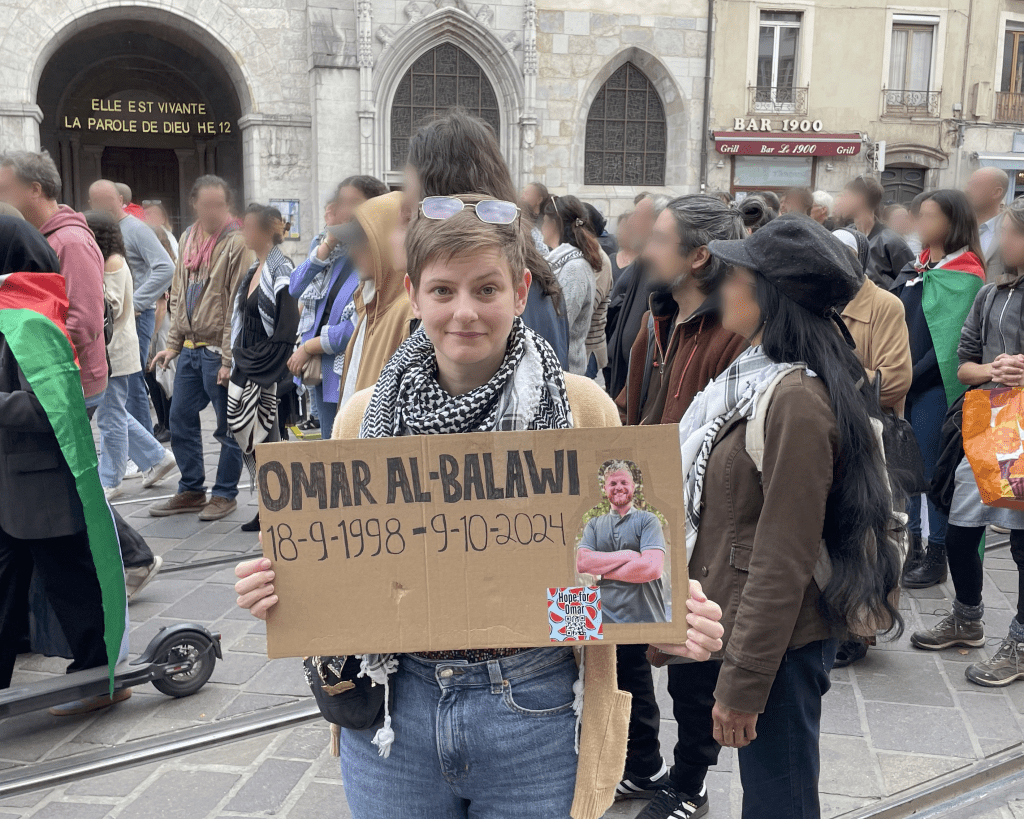

During these months, I attended at least one protest for Palestine each month in my city. I felt some relief in this outlet for my grief and anger. There was hope for me in being able to walk and shout with others and in seeing the diversity of the crowds that showed up. I also believed it was important for trying to bring more visibility and awareness. I donated some money to aid organizations or Palestinians’ GoFundMe accounts. I constantly shared stories and posts on my social media surrounding my new politicization. At first, I shared posts with news from Palestine or about the involvement and complicity of the US, and quotes that resonated with me about grief, hope, solidarity, and liberation. Later, I began to share about other issues like workers rights, the harms of capitalism, the wealth gap, colonization, climate change, the Congo, and Sudan. I wrote an essay about collective grief and what I was experiencing as I witnessed what was happening in Gaza and then another about conscious consumerism and boycotting. I received very little interaction with anything political I was sharing. There weren’t even angry or disagreeing messages and comments — mostly just silence. I did engage in some conversations with friends or family about Gaza and how it was changing me, though in some cases I did not know how to navigate them very well.

I wrote in my journal on March 24, 2024:

My friends, family, and therapist all tell me to look less — if it’s making me so unhappy. “Protect your peace. You can’t really do anything to help them.” It rings false for me. It falls short. I will not close my eyes or bury my head and I will not remain silent. How can I? Why should I? I would rather feel this than happiness via ignorance. I feel I am struggling to reach a new understanding or a new “calling” for myself. I will come out stronger and more centered on love and justice.

Slowly, I began to emerge from despair and nihilism — rooting myself again in love, finding hope in the struggle for collective liberation, and believing that all of our individual actions combined can make a difference. It was civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer who said, “Nobody’s free until everybody’s free.” I came to understand the deep interconnectivity of all things and the truth of these words. Palestine shined a light for me to see the links between all struggles of oppression. It laid bare how intersections of white supremacy, cisheteropatriarchy, capitalism, imperialism, and colonization were playing out in Gaza and all over the world. There was a spark of hope resting in the knowledge of this darkness – we can get free together.

In June of 2024, I wrote another essay entitled “Please Join the Revolution: An invitation from a newly radicalized white American”. I had learned from Angela Y. Davis that, “radical simply means grasping things at the root.” I desired to dig deep into the dirt of this broken society and grasp at the roots — understanding and then fighting against the powers of oppression that grow deep beneath us. I recorded myself reading my essay while wearing a Palestinian keffiyeh. I wanted to speak to those who, like me previously, were simply uninformed or too overwhelmed to engage with the news and let themselves be moved into action. The words came from the truest depths of me and still I felt fear and doubt in sharing them. What right did I have to invite anyone to a revolution I just joined? Would this even make any difference? I always landed back on the idea that if it made an impact for just one person, it was worth it. I had come to believe that silence in the face of injustice was complicity so I would not remain silent.

Still, my actions never felt good enough. Even as I tried to tell myself that I could only do what I could do, I was wracked with grief and guilt. Any relief I got from taking action was fleeting. On Instagram (again), I came across the work of Black womanist teacher, Nikki Blak, and saw that she was offering a 6 month course called the Wayfinder activism incubator. One part of the site about the program read:

Who are you meant to be in liberation? What is the work that you’re being called to do? If you don’t know and want to find out, I’ll be in the Wayfinder Activism Incubator to guide you toward discovering the answers. Some of the first things we clean up in the Wayfinder Activism Incubator are white guilt, shame and the allure of activist martyrdom, which is rooted in capitalist, ableist, cisheteropatriarchy.

With the help of an intimate community and a radical liberatory curriculum you’ll discover your work in anti-oppression, decolonization, and racial justice activism and be supported on your climb to the next level in your relationship with your revolutionary self in radical liberation.

Sign me up. This sounded like exactly what I wanted and needed to help orient myself in my new worldview with a northstar of collective liberation. Nikki met our cohort in the virtual space with the same grace, kindness, and honesty that I had found within the words of the Black intersectional feminist writers I’d begun learning from. She came with an eagerness to share her wisdom of how we as white women could engage in the work of collective liberation — not as allies but as co-conspirators. This idea is reflected in the quote from Lilla Watson: “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

We had a book list, additional online teachings and content, an online social portal, and weekly video sessions together to explore what we were learning (or struggling with) and receive teachings and support from Nikki. Additionally, we were each to complete some form of an activist project during the course. There is so much that I learned and wrestled with during this time that helped reshape my thoughts, actions, and intentions around activism and liberatory work.

We dug deeply into what Nikki calls the “Tenets of Whiteness” which reflected some of the ideas that I had first encountered within the book White Women. These are ways of existing and operating within white western culture that are portrayed as natural or innate behavior until they are pointed out. Then suddenly, the veil is lifted and you recognize that these are cultural choices. There is nothing innate about a behavior like white niceness, that values keeping the “peace” at the expense of truth-telling or calling out harm. Speaker and coach, Jessica Dickson, says, “Niceness forces us to abandon ourselves and our truth in favor for what will keep things calm.” White niceness is what keeps us silent when family members or co-workers make racist or sexist “jokes”. White niceness says it is impolite to point out to people that their tax dollars are used to fund military violence around the world while American healthcare buries people under mountains of medical debt. This kind of truth is inconvenient and painful and a nice person simply does not discuss such things. If you’re interested in learning more about niceness and the many other tenets that uphold whiteness, you can subscribe to Nikki’s patreon to read her full essay.

Our conversations also helped me to reframe my thoughts around violence. Nikki asked us questions like: How do you define violence? Where did you learn that definition? Who does that definition include and exclude? We pondered together over the violence of systems that uphold cishetero patriarchal white supremacy. CDC.gov states that Black women are three times more likely than white women to die from pregnancy-related causes. Why do we not consider this as violence? Why are the same politicians who are so quick to condemn “political violence” when a person in a position of power is targeted then so willing to pass legislation that will harm millions in the US or abroad? On her Instagram, Nikki writes: “Who is allowed to be violent without apology and whose violence we tolerate and even celebrate is almost entirely determined by race and gender… Violence is all around us. We have simply rationalized a hierarchy that makes violence from certain people more visible and less acceptable.” I am not interested in a selective moral rage that, for example, demonizes rioters while saying nothing of the systemic oppressions that led to that boiling point.

One of my favorite things we learned about was freedom dreaming and the use of the radical imagination. In his book Freedom Dreams:The Black Radical Imagination, Robin D.G. Kelley traces the history of the Black struggle for liberation and speaks of the importance of imagination within different movements. From music and poetry to community building, the Haitian revolution, and abolition — all of it starts with imagining a world that is different from the one we currently inhabit. Nikki spoke multiple times of how the world we live in is the product of imagination. We are often taught “this is just the way things are” when in fact the truth is actually that “we are living in someone’s imagination.” Our society and the powers that rule it are not innate inevitabilities. This means that by engaging with our own radical imaginations to dream of a more just and liberated future, we can help create something different, something more beautiful. This line of thinking gives me hope even amongst our current struggles against oppression.

I could go on and on about what I learned during those 6 months and how it encouraged and rooted me as an activist and helped me believe that my actions were in fact good enough. Towards the end of our time together, Nikki encouraged us to write an activist statement to center our work and call out what we believe and how we will act. Here is part of what I wrote:

I desire to co-create a more beautiful, just world of collective liberation through storytelling. I believe in the inherent worth and dignity of every human being, along with our deep interconnectedness. I hold true, as Fannie Lou Hamer said, “Nobody’s free until we’re all free.” As a white American woman, I recognize my privileges and seek to leverage them by elevating the voices and stories of the historically oppressed people of the global majority. I allow love to lead me and further ground myself in empathy, humility, and truth.

During the course, the project I did was a mutual aid campaign for a family in Gaza. While I visited my home town in the summer of 2024, I attended a meeting of a group in support of Palestine and met a Palestinian-American woman. Some months later she reached out to me to ask if I would be willing to help organize the campaign for her friend. I hadn’t yet chosen a project and decided to take on this opportunity. This is how I met Omar Al-Balawi. We spoke for the first time on September 15, 2024 and he began to share his story with me.

At 26 years old, Omar had spent his early 20s building up his career as an English teacher in Gaza and working to create a beautiful life and future for himself. He spent 3 years building his own home, which he had to evacuate almost immediately at the beginning of Israel’s assault in October 2023 and was later bombed. In August of 2024, his family’s home was targeted by Israeli rockets which killed his older brother, his sister-in-law, and his niece: Mohammed, Hannen, and Selia. Throughout everything, Omar continued teaching English, through the UK-based Hands Up project, and working with other non-profits to help provide aid in northern Gaza, where Omar and his family remained.

Omar and I spoke everyday after we met. We got to know each other as genuine friends, talking about many different subjects, along with bouncing around ideas to raise funds for the campaign. His is a kind, gentle, and beautiful soul. From the beginning of our conversations, Omar was clear and accepting of the fact that he may die at any time. As escalation began in Lebanon and talk began to circulate of a new ground invasion in the north of Gaza Omar wrote to me: “I may die today or tomorrow. If that happens, please don’t stop sharing my stories. Let everyone know me and what happened in Gaza.” I assured him that I would not stop sharing his story and, as always, he then apologized for speaking of such sad matters – never wanting to make me feel upset or anxious.

On October 5th, Israel began their ground invasion and papers fell from the sky telling all civilians to evacuate to the south, their clear goal to ethnically cleanse the area and occupy the land. Omar and his family, like many others chose to remain in their home, as it was all they had and they knew that there was really nowhere safe for them to go. Omar also felt a duty to help resist the occupation by remaining in the north. He sent me chilling voice memos of the nearby sounds of tanks and gunshots.

As the army approached closer and closer to their home, they decided to prepare for evacuation. He sent me a picture of their packed bags – ready to leave at a moment’s notice and spent some moments on a video call with me to tell me if they left he might not be in contact for a few days. We continued to speak about the approaching army and ideas for the mutual aid campaign. Just hours after we’d last spoken, I was on a bus heading home after spending the day in a nearby city when comments on a recent Instagram post of Omar’s started pouring in, stating he was dead. I stared at my phone in shock, not wanting to believe what I was seeing. I wrote to his friends for more information, and cried quietly for the remaining hour of the bus ride. Despite knowing the bleak reality of the situation I still so hoped that my friend would survive, that maybe one day we could even meet. But this was not to be.

On October 9, 2024 Omar was shot and killed by an Israeli drone while near the window of his family’s home. Just two months after the death of his brother, sister-in-law, and niece. I cannot imagine the immense and heavy grief of his family, friends, students, and community compounded with a year of unending loss. I knew Omar only the last month of his life and still felt his loss deeply. How fortunate I was to meet him and call him a friend. How beautiful to encounter a heart that had endured so much war and struggle and loss in a short 26 years of life and yet still showed up consistently with kindness, grace, hope, generosity, and love. Omar never set foot outside of Gaza, but I carry him with me now. As long as I draw breath his story, though one of thousands of Gazans, will travel far and wide. (Rest in power and peace, dear friend, and know that I will be true to my word.)

As I shared about Omar on Instagram I began to receive messages from friends and even students of his. One woman that wrote to me was a classmate of his named Dina. I had written a poem about Omar and she wanted to share with me her own poem she’d written about him. We have continued talking over the past year and I have helped support her family through mutual aid fundraising as they have been displaced multiple times and struggled to find and purchase food and other necessary items. I have made connections with others in Gaza as well and seek to amplify their voices, stories, and writing.

I continue learning, growing, decolonizing, and divesting from white supremacy culture each day as I am able. I have been fortunate enough to continue one-on-one coaching with Nikki Blak and am endlessly grateful for her voice and the ways she challenges and emboldens me to use my voice and privilege as a white American woman to speak truth to power. I don’t know all the places where my activism will take me, but I’m thrilled to be a part of Her Times where I can work towards my proposed mission of “elevating the voices and stories of the historically oppressed people of the global majority.” I hope that my story and other peoples’ stories that I share in the future will encourage more people to look outside of their bubbles, grasp from the roots, and find their own pathways to actions supporting collective liberation.

This essay is not intended to be a blueprint for how to engage in the work of collective liberation and divestment from white supremacy. Each journey is different because our personalities, families, resources, and experiences are different. Rather, I hope that you will consider what actions you may take in your own life in radical pursuit of collective liberation. You are stronger and more powerful than you have been made to believe. If this work is calling to you, I hope you will answer the call with humility, curiosity, hope, and endless love.